Turn Waste into Profit: An Expert’s 2026 Guide to the Circular Economy in Building Materials

Dezembro 31, 2025

Resumo

The global construction industry, a significant contributor to resource depletion and waste generation, stands at a critical juncture in 2026. This analysis examines the transition from a linear "take-make-waste" paradigm to a circular economy in building materials, with a particular focus on its implementation within the rapidly developing regions of Southeast Asia and the Middle East. It investigates the principles of designing for disassembly, reuse, and high-value recycling, positing that such a shift is not merely an environmental imperative but a substantial economic opportunity. The document explores the practical application of circular principles through the utilization of industrial by-products and demolition waste, such as fly ash, slag, and crushed concrete, as viable raw materials. It highlights the pivotal role of modern manufacturing technologies, specifically concrete block making machines, in transforming these waste streams into valuable, high-performance construction components. By converting liabilities into assets, businesses can achieve reduced operational costs, enhanced resource security, and a competitive advantage in a market increasingly governed by sustainability mandates.

Principais conclusões

- Embrace waste as a resource to lower material procurement costs.

- Design buildings for future disassembly to maximize material recovery.

- Adopt technologies that process recycled and secondary raw materials.

- Explore the circular economy in building materials to create new revenue.

- Invest in quality control to ensure recycled materials meet standards.

- Leverage green building certifications to enhance marketability.

Índice

- The Moral and Economic Case for a Circular Shift in Construction

- Foundational Pillars of a Circular Built Environment

- Turning Waste into Wealth: A Catalogue of Circular Building Materials for 2026

- The Heart of the Operation: Advanced Machinery for a Circular Future

- Real-World Application: Circular Economy Case Studies

- Overcoming the Hurdles: A Pragmatic Look at Implementation Challenges

- Building the Business Case: The Financial Logic of Circularity

- Gazing into the Future: Innovations on the Horizon

- Perguntas frequentes (FAQ)

- A Concluding Reflection on Our Built Future

- Referências

The Moral and Economic Case for a Circular Shift in Construction

The story we have told ourselves about progress is deeply intertwined with the act of building. We see it in the rising skylines of Dubai and the sprawling urban expansion of Ho Chi Minh City. Yet, this narrative of growth has carried with it a profound, often unacknowledged, cost. The construction sector has historically operated on a linear model, a straight line from extraction to demolition. We take resources from the earth, make them into buildings, and when their useful life concludes, we dispose of them. This system, for all its apparent simplicity, is predicated on the flawed assumption of infinite resources and infinite space for waste. As we navigate the realities of 2026, the physical and economic limits of this assumption are becoming starkly apparent. The challenge before us is not to cease building, but to reimagine the very nature of how we build, moving from a line to a circle.

This calls for a shift in our fundamental understanding of value. What if a demolished building was not an endpoint, but a beginning? What if the by-products of our industrial processes were not waste to be managed, but resources to be capitalized upon? This is the central proposition of the circular economy in building materials. It is an economic model that seeks to eliminate waste and promote the continual use of resources. It is a framework that requires us to think like nature, where the concept of waste does not exist. For the business owner, the contractor, or the developer in Southeast Asia or the Middle East, this is not a distant philosophical concept. It is an immediate, practical, and profitable pathway to resilience and competitive advantage in a world of increasing resource scarcity and environmental regulation.

Understanding the Linear "Take-Make-Waste" Model

To appreciate the revolutionary nature of the circular economy, one must first deeply understand the mechanics and consequences of the linear system it seeks to replace. Imagine the life cycle of a typical building constructed in the late 20th century. Its story begins in a quarry, a forest, or a mine. Raw materials—limestone for cement, iron ore for steel, sand and gravel for aggregate—are extracted from the earth, an energy-intensive process that often leaves lasting scars on the landscape. These materials are then transported, often over great distances, to factories where they are processed into finished products: concrete, steel beams, glass panels.

These components are then assembled on-site into a building designed for a specific purpose and a finite lifespan. During its operational life, it consumes energy and water and requires maintenance. But the critical moment in the linear story is its end. When the building is deemed obsolete, functionally or economically, the demolition crews arrive. The structure is brought down, reduced to a mixed pile of rubble. Some high-value metals might be salvaged, but the vast majority—tonnes of concrete, brick, wood, and insulation—is loaded onto trucks and hauled to a landfill. There, it is buried, its material value lost forever, occupying land and potentially leaching substances into the soil and groundwater. This is the "take-make-waste" trajectory in its starkest form. It is a one-way street, efficient in the short term but profoundly inefficient and unsustainable when viewed through a wider lens of resource stewardship and long-term economic health. The model treats natural capital as income rather than as an asset to be preserved, a fundamental accounting error that we are only now beginning to rectify (Pearce & Turner, 1990).

The Environmental and Economic Costs of Linear Construction

The consequences of this linear approach are not abstract. They manifest as tangible costs, both to the environment and to the bottom line. Environmentally, the construction industry is responsible for a staggering share of global impacts. It accounts for approximately 40% of global energy consumption and 38% of total greenhouse gas emissions (UNEP, 2021). The extraction of virgin materials degrades ecosystems, while the mountains of construction and demolition waste (CDW) place immense pressure on landfill capacity, a particularly acute problem in densely populated urban centers across Southeast Asia.

Economically, the linear model creates immense vulnerability. Businesses are exposed to the volatility of raw material prices, which are subject to geopolitical tensions, supply chain disruptions, and increasing extraction costs. When you rely solely on virgin materials, your production costs are tethered to forces far outside your control. Furthermore, landfilling waste is not free. Tipping fees are a direct operational expense, and as landfills reach capacity and environmental regulations tighten, these costs are projected to rise significantly. In this model, waste is purely a liability on the balance sheet. It represents a triple loss: the initial cost of purchasing the material, the cost of disposing of it, and the lost opportunity to recover any of its inherent value. A system that discards millions of tonnes of potentially useful materials is, by any rational economic measure, a system that is failing.

Defining the Circular Economy in Building Materials

In response to the failings of the linear model, the circular economy offers a compelling and restorative alternative. It is not simply about recycling more. It is a holistic redesign of the entire system, guided by three core principles: designing out waste and pollution, keeping products and materials in use at their highest possible value, and regenerating natural systems (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2013).

Let's translate this into the context of building materials.

- Designing out waste and pollution: This begins at the drawing board. It involves choosing materials that are non-toxic and can be easily separated. It means designing buildings that are adaptable and can be deconstructed rather than demolished. Think of a structure assembled with bolts and screws instead of permanent adhesives and welds.

- Keeping products and materials in use: This is the heart of the circular flow. It prioritizes reuse of components first (e.g., salvaging steel beams or facade panels for use in a new building), then refurbishment, and finally, recycling materials back into new products. A concrete beam might be crushed to become aggregate for new concrete, or industrial fly ash could be used to create durable concrete blocks. The goal is to keep the materials circulating within the economy, preventing them from ever becoming waste.

- Regenerating natural systems: In the context of construction, this can mean using bio-based materials like sustainably sourced timber or innovative materials that actively absorb CO2. It means creating buildings that enhance their local environment, for example, through green roofs that manage stormwater and reduce the urban heat island effect.

The circular economy in building materials, therefore, is an industrial system that is restorative and regenerative by design and intention. It replaces the "end-of-life" concept with restoration, shifts towards the use of renewable energy, eliminates the use of toxic chemicals, and aims for the elimination of waste through the superior design of materials, products, systems, and business models.

Foundational Pillars of a Circular Built Environment

Transitioning to a circular model in construction is not a single action but a sustained commitment to a new set of operating principles. It requires a fundamental shift in how we conceive, design, build, and deconstruct our built environment. These pillars form the intellectual and practical foundation upon which a truly circular construction industry can be built. They are not independent strategies but an interconnected framework where each element reinforces the others.

Designing for Disassembly and Adaptability

The capacity to close material loops in the future is determined almost entirely by decisions made today, at the design stage. Designing for Disassembly (DfD) is a design philosophy that explicitly plans for the eventual deconstruction of a building and the recovery of its components. It is the antithesis of the conventional design approach, which often prioritizes speed of construction and initial cost, inadvertently creating structures that are impossible to take apart without destroying their constituent materials.

Consider the analogy of furniture. A piece of flat-pack furniture is designed to be assembled with simple tools and can, with relative ease, be disassembled for moving or disposal. Conversely, a piece that is heavily glued and nailed together can only be broken apart, destroying its components in the process. DfD applies the flat-pack logic to buildings. This involves:

- Mechanical vs. Chemical Connections: Using bolts, screws, and clips instead of permanent adhesives, mortars, and welds. This allows components like facade panels, structural beams, and interior walls to be detached intact.

- Material Layering: Avoiding composite materials where different elements are fused inseparably. Instead, designers should layer materials so they can be peeled away one by one. For example, a roofing system might be designed with distinct, separable layers for waterproofing, insulation, and structure.

- Standardization and Modularity: Creating components with standard dimensions and connection points. This increases the likelihood that a salvaged beam or window from one building can be easily integrated into another.

- Accessibility: Ensuring that connection points are accessible for maintenance and eventual disassembly.

Beyond disassembly, designing for adaptability is equally important. A building's use can change dramatically over its lifespan. A structure designed with adaptable floor plans, movable partitions, and robust structural capacity can be transformed from an office to residential units, or from a retail space to a school, extending its useful life and delaying the need for demolition.

Prioritizing Reuse and Repair

The energy and resources embedded in a building component represent a significant investment. The circular economy dictates that we should seek to preserve this investment for as long as possible. Before considering recycling, we must exhaust the options of repair and reuse. This creates a value hierarchy:

- Repair: Extending the life of a component in its current application. This could be as simple as replacing a broken seal on a window or refinishing a wooden floor.

- Reutilização: Taking a component from one building and using it for the same purpose in a new building. A classic example is salvaging historic bricks or structural steel beams for a new project. This preserves the highest possible value, as the component's form and function are maintained with minimal reprocessing.

The market for salvaged building materials is a cornerstone of this principle. In many regions, this is still a niche industry, but it holds immense potential for growth. It requires the development of infrastructure for careful deconstruction (as opposed to brute-force demolition), as well as platforms for cataloging, storing, and trading salvaged components. For businesses in the Middle East and Southeast Asia, establishing operations in "urban mining"—the process of reclaiming materials from the existing building stock—can become a profitable new venture.

The Role of Recycling and Upcycling

When repair or reuse are not feasible, recycling becomes the next best option. However, not all recycling is created equal. It's useful to distinguish between downcycling, recycling, and upcycling.

- Downcycling: Transforming a material into a new product of lower quality and reduced functionality. A common example is crushing high-strength concrete into low-grade fill material for roadbeds. While better than landfilling, downcycling diminishes the material's value.

- Recycling: Transforming a material back into the same product or a product of similar value. A key example is melting down scrap steel to produce new structural steel, which can be done repeatedly without loss of quality.

- Upcycling: Transforming a waste material or by-product into a new material or product of higher quality or value. This is where significant innovation is occurring. For instance, using waste plastic to create durable, lightweight facade panels or using industrial fly ash, a by-product of coal combustion, as a high-performance replacement for cement in concrete.

The goal within a circular economy is to push as much material as possible towards high-value recycling and upcycling, preserving its intrinsic properties and economic worth. This requires sophisticated sorting and processing technologies, which we will explore later.

Material Passports: The Digital DNA of Building Components

One of the greatest barriers to reuse and recycling is a lack of information. When a building is demolished, we often don't know the exact composition, performance characteristics, or potential hazards of the materials within it. Material passports are a proposed solution to this problem (Debacker & Manshoven, 2016).

A material passport is a digital data set that describes the characteristics of materials in a product or building. It contains information on the composition, origin, recycled content, disassembly instructions, and potential for reuse and recycling. Think of it as a "digital twin" for every component in a building, from a steel beam to a carpet tile.

By attaching this data to the physical materials, we create a permanent record that travels with them throughout their life cycle. When the building is ready for renovation or deconstruction, the material passports can be accessed to identify which components can be safely reused, which can be recycled, and how to do so effectively. This transforms demolition from a guessing game into a precise, data-driven process of urban mining. For a developer, having a building with comprehensive material passports could increase its residual value, as the materials are no longer an unknown liability but a documented asset. The implementation of such systems is still in its early stages in 2026, but it represents a critical piece of the digital infrastructure needed for a truly circular built environment.

Turning Waste into Wealth: A Catalogue of Circular Building Materials for 2026

The abstract principles of the circular economy become concrete reality when we examine the specific material streams that can be diverted from landfills and reintegrated into the production cycle. For businesses in the construction sector, understanding these materials—their sources, their processing requirements, and their potential applications—is the key to unlocking new efficiencies and revenue streams. The following catalogue details some of the most significant circular building materials available in 2026, with a particular focus on those relevant to Southeast Asia and the Middle East.

Concrete and Demolition Debris: From Rubble to Resource

Concrete is the most consumed man-made material on earth, and consequently, it is the largest component of construction and demolition waste (CDW). Traditionally, demolished concrete has been viewed as a low-value material, often crushed and used as backfill or road base—a clear case of downcycling. The circular approach, however, seeks to elevate its value by processing it into Recycled Concrete Aggregate (RCA).

The process involves several key steps. First, the demolished concrete must be separated from other waste streams like wood, plastic, and metal. Powerful magnets are used to remove reinforcing steel (which is itself a highly recyclable material). The concrete is then fed into primary and secondary crushers, which break it down into specified sizes. Advanced systems may also use screening, air separation, or water-based methods to remove contaminants like gypsum and brick, which can affect the quality of the final product.

The resulting RCA can be used to replace a portion of the virgin aggregate (sand and gravel) in new concrete mixes. The table below compares the typical properties of virgin aggregate with those of good quality RCA.

| Property | Virgin Natural Aggregate (NA) | Recycled Concrete Aggregate (RCA) | Implications for Concrete Production |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Quarries, riverbeds (finite) | Demolished concrete structures | RCA reduces the need for virgin material extraction. |

| Density | Typically 2.6 – 2.8 g/cm³ | Typically 2.2 – 2.5 g/cm³ | RCA is lighter, which can reduce the dead load of a structure. |

| Absorção de água | 0.5% – 2.0% | 3.0% – 9.0% | Higher absorption must be accounted for in the mix design to maintain the correct water-to-cement ratio. |

| Composition | Natural rock and mineral fragments | Crushed concrete, includes original aggregate and adhered cement mortar | The adhered mortar is porous and weaker than the original aggregate, affecting overall performance. |

| Cost | Subject to market volatility, transport costs | Lower material cost, but processing adds expense. Can be very low if sourced on-site. | RCA can offer significant cost savings, especially on large projects with on-site crushing. |

While RCA has historically been limited to non-structural applications due to concerns about its higher water absorption and the variability of the old cement paste attached to it, advancements in processing and concrete mix design are changing this. By carefully controlling the quality of RCA and adjusting mix proportions—for example, by using water-reducing admixtures or adding supplementary cementitious materials—it is now feasible to produce high-performance structural concrete with significant RCA content (Obla, 2021). For a contractor, the ability to crush concrete from a demolition site and reuse it in the foundations of the new building on the same site represents a perfect closed loop, eliminating transport costs and landfill fees.

Industrial By-products: Fly Ash, Slag, and Silica Fume

Some of the most valuable circular materials are not sourced from old buildings but are the by-products of other industrial processes. These materials, known as Supplementary Cementitious Materials (SCMs), can replace a significant portion of the Portland cement in a concrete mix. This is hugely important because cement production is incredibly energy-intensive and is responsible for about 8% of global CO2 emissions. Using SCMs not only diverts waste from landfills but also dramatically reduces the carbon footprint of concrete.

- Cinzas volantes: This is a fine powder captured from the exhaust gases of coal-fired power plants. For decades, it was considered a waste product requiring disposal. However, it exhibits "pozzolanic" activity, meaning that in the presence of water and calcium hydroxide (a by-product of cement hydration), it forms compounds with cementitious properties (Mehta, 2014). Replacing 20-30% of cement with fly ash can improve the long-term strength and durability of concrete, enhance its workability, and significantly reduce its permeability to water and chlorides, making it ideal for the harsh, saline environments common in the Middle East. Many modern block making machines are explicitly designed to handle mixes with high fly ash content .

- Ground Granulated Blast-furnace Slag (GGBS): GGBS is a by-product of iron manufacturing in a blast furnace. The molten slag is rapidly quenched with water to form a glassy, granular material, which is then ground into a fine powder. Like fly ash, GGBS has cementitious properties. Concrete made with GGBS has a lighter color, excellent resistance to chemical attack, and a lower heat of hydration, which is beneficial for mass concrete pours to prevent cracking. Replacement levels can be as high as 70% in certain applications.

- Sílica de fumo: A highly effective but more niche SCM, silica fume is an ultra-fine powder collected as a by-product of silicon and ferrosilicon alloy production. It is an extremely reactive pozzolan. Adding just a small amount (5-10% by weight of cement) can dramatically increase the strength and durability of concrete, creating high-performance or ultra-high-performance concrete with compressive strengths exceeding 100 MPa.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these primary SCMs.

| Supplementary Cementitious Material (SCM) | Source | Typical Replacement of Cement | Key Benefits to Concrete |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fly Ash (Class F) | Coal-fired power plants | 15% – 35% | Improved workability, higher long-term strength, reduced permeability, lower heat of hydration. |

| Ground Granulated Blast-furnace Slag (GGBS) | Iron and steel manufacturing | 30% – 70% | Higher resistance to sulfate and chloride attack, lighter color, improved durability, lower heat of hydration. |

| Silica Fume | Silicon alloy production | 5% – 15% | Very high strength, significantly reduced permeability, increased abrasion resistance. |

For a concrete or block producer, integrating these SCMs into their production process is a direct path to creating a greener, higher-performance, and often more cost-effective product.

The Untapped Potential of Timber, Metals, and Plastics

While concrete and SCMs represent the largest volume of circular materials, other waste streams also offer significant value.

- Metals: Steel and aluminum are among the most recyclable materials used in construction. The recycling process for metals is highly efficient and can be repeated almost indefinitely without any loss of quality. Structural steel beams, reinforcing bars (rebar), window frames, and piping can all be salvaged, melted down, and reformed into new products, saving up to 95% of the energy required to produce them from virgin ore. The economic incentive for metal recycling is already strong, and well-established markets exist.

- Timber: Wood from demolition can be recovered for a variety of uses. High-quality, large-dimension beams can be salvaged and reused directly. Lower-quality wood can be chipped and used to manufacture engineered wood products like particleboard or medium-density fiberboard (MDF). Even wood waste that cannot be used in manufacturing can be repurposed as biomass fuel, displacing fossil fuels.

- Plastics: Construction is a major consumer of plastics, from PVC pipes and insulation to flooring and vapor barriers. Plastic waste is a complex challenge due to the many different polymer types, which are often difficult to separate. However, innovation is driving new solutions. Some companies are now converting mixed plastic waste into durable, lightweight bricks, blocks, and lumber substitutes suitable for applications like landscaping, fencing, and non-structural elements.

By viewing every material stream flowing out of a demolition site as a potential input for a new process, we fundamentally change the economics of waste. Rubble becomes a quarry, and industrial exhaust becomes a cement kiln.

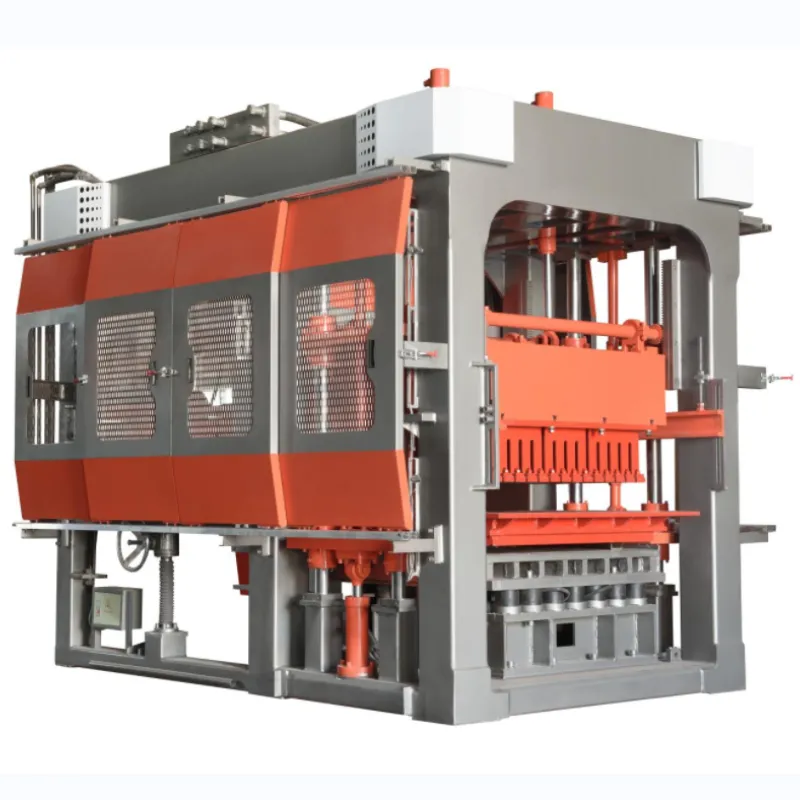

The Heart of the Operation: Advanced Machinery for a Circular Future

The vision of a circular economy in building materials, where waste is transformed into valuable products, is not just a theoretical ideal. It is made possible by robust, efficient, and sophisticated machinery. At the center of this transformation, particularly for materials like recycled aggregate and industrial by-products, is the modern concrete block making machine. These machines are the engines that convert carefully proportioned mixes of cement, sand, water, and circular raw materials into high-quality, uniform masonry units. Understanding their function, types, and capabilities is essential for any business looking to enter or expand within this growing market.

How Automatic Block Making Machines Transform Waste

The process of turning waste into a block is a marvel of modern engineering. Let's walk through the steps. It begins with raw material preparation. Waste materials like crushed concrete (RCA), fly ash, or slag are stored in separate hoppers. A computerized batching plant precisely weighs and measures each component—including cement, virgin sand (if needed), water, and chemical admixtures—according to a specific mix design. This precision is critical for ensuring consistent quality.

The batched materials are then transported via conveyor belt to a mixer, which blends them into a homogenous, "zero-slump" concrete mix. This mix is stiff, with just enough water for hydration, which is necessary for the block-making process. The mix is then conveyed to the block machine's hopper. From here, it is fed into a steel mould, which defines the shape of the block (e.g., hollow block, solid block, or paving stone).

The magic happens next. The machine applies a combination of intense vibration and hydraulic pressure. The vibration helps the stiff concrete mix consolidate and fill every corner of the mould, eliminating air pockets. Simultaneously, a powerful hydraulic press compacts the material from above. This dual action of vibration and compression is what gives the resulting "green" block its initial strength and precise dimensions. The mould is then lifted, and the newly formed blocks are pushed out onto a pallet. These pallets are transferred to a curing area, where the blocks gain strength over several days as the cement hydrates. High-production plants use automated stackers and curing racks to manage this process efficiently. This entire cycle, from feeding the mould to ejecting the finished blocks, can take as little as 15-25 seconds with a high-capacity machine like a QT10-15 model .

Comparing Static vs. Mobile Block Pressing Machines

Concrete block machines come in various configurations, but a primary distinction is between large, stationary plants and smaller, mobile "egg-layer" machines. The choice between them depends heavily on the scale of operation, capital investment, and target market.

| Caraterística | Static Hydraulic Block Machine Plant | Mobile "Egg-Layer" Block Machine |

|---|---|---|

| Funcionamento | Fixed in one location as part of a larger production line with batching, mixing, and curing systems. | Moves around a concrete floor, "laying" blocks directly onto the ground as it goes. |

| Production Capacity | Very high. Can produce 15,000 to over 100,000 blocks per 8-hour shift. | Lower. Typically produces 1,000 to 5,000 blocks per 8-hour shift. |

| Automation | Highly automated, often with PLC control for batching, pressing, and handling. Requires fewer operators per block produced. | Typically semi-automatic or manual. Requires more labor for mixing, moving the machine, and collecting cured blocks. |

| Product Variety | Can produce a vast range of products (hollow, solid, pavers, kerbstones) by changing moulds. Quality and consistency are very high. | Limited to a smaller range of basic block types. Consistency can vary more than with static machines. |

| Infrastructure Needs | Requires significant investment in a factory building, concrete foundations, silos, and automated handling systems. | Requires only a large, flat concrete slab for operation and curing. No fixed infrastructure needed. |

| Ideal Application | Large-scale commercial production for major construction suppliers and large projects. | Small-scale start-ups, on-site production for specific projects, or serving rural/remote areas. |

For a business serious about capitalizing on the circular economy, a static hydraulic plant offers the control, consistency, and scale necessary to process diverse waste streams into certified, high-quality products. A reliable fully automatic concrete block making machine line is the cornerstone of such an operation, providing the efficiency needed to compete in the modern construction market.

Key Features to Look for in a 2026 Block Machine

When investing in a block making machine, especially for use with circular materials, certain features are paramount.

- Robust Vibration System: The machine must have a powerful and well-engineered vibration system. Look for machines with variable frequency control. This allows the operator to fine-tune the vibration amplitude and frequency to suit different mix designs. A mix with a high percentage of fly ash, for instance, may require a different vibration pattern than one with coarse recycled aggregate to achieve optimal compaction. Models with both table vibration and mould head vibration can provide superior results.

- High-Pressure Hydraulic System: A strong hydraulic system ensures high compaction force, which is crucial for producing dense, strong blocks with low porosity. This is particularly important when using materials like RCA, as high pressure helps to overcome the inherent porosity of the attached mortar. Look for machines using reputable hydraulic components from brands like Bosch Rexroth or Yuken.

- Intelligent PLC Control: A modern machine should be controlled by a Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) with a user-friendly Human-Machine Interface (HMI) or touchscreen. This allows for the storage of different mix recipes and machine parameters, ensuring repeatability and consistency. It also provides diagnostics for troubleshooting and simplifies operation. Top-tier machines often use PLCs from manufacturers like Siemens or Mitsubishi.

- Durable, Quick-Change Moulds: The mould is the part of the machine that experiences the most wear. It should be made from high-quality, wear-resistant steel that has undergone heat treatment processes like carburizing to harden the surface. A system that allows for quick and easy mould changes is also critical for businesses that want to produce a variety of products efficiently.

- Forced Material Feeding System: A simple gravity-fed system may not be sufficient for the often less-flowable mixes containing recycled materials. A forced feeding system with rotating agitators inside the feed box ensures that the mould is filled evenly and quickly, which is essential for uniform block density and a fast cycle time.

Raw Material Compatibility: A Crucial Consideration

The ultimate success of a circular block-making venture depends on the machine's ability to effectively process a wide range of raw materials. The table below outlines common circular inputs and considerations for their use.

| Circular Raw Material | Descrição | Key Considerations for Block Production |

|---|---|---|

| Recycled Concrete Aggregate (RCA) | Crushed and graded concrete from demolition. | Higher water absorption requires careful water control in the mix. Can lead to slightly lower strength if not managed. Requires a robust machine that can compact less workable mixes. |

| Fly Ash | Fine powder from coal combustion. | Acts as a cement replacement. Improves long-term strength and durability but can slow down initial setting time. The mix may be "stickier." |

| Crushed Glass (Cullet) | Clean, crushed glass, often ground to a fine powder (pozzolan). | Can replace a portion of sand or cement. Can cause an alkali-silica reaction (ASR) if not properly managed, but fine grinding mitigates this risk. |

| Foundry Sand | Waste sand from metal casting processes. | Can be used as a fine aggregate replacement. Must be tested for contaminants. Its fine, uniform nature can affect mix workability. |

| Mine Tailings | Waste material from mining operations. | Potential use as fine aggregate. Requires extensive testing for heavy metals or other hazardous substances. Varies greatly by source. |

| Plastic Waste | Shredded or melted plastic waste. | Used in specialized block types. Not suitable for standard concrete block machines. Requires a different type of thermal-press technology. |

Before investing, a potential buyer should discuss their intended raw materials with the machine manufacturer. Reputable manufacturers can provide guidance on mix designs and may even test a customer's specific materials to confirm compatibility and predict the final product's performance . This due diligence ensures that the chosen technology is a true asset in the journey toward a profitable, circular business model.

Real-World Application: Circular Economy Case Studies

The principles of a circular economy in construction are not confined to academic papers or policy documents. Across Southeast Asia and the Middle East, pioneering governments and companies are actively implementing these ideas, creating tangible examples of how circularity can be integrated into a nation's development strategy. These case studies provide valuable lessons and a clear demonstration of the model's viability.

Singapore's Zero-Waste Masterplan: A National Push for Recycled Aggregates

Singapore, a dense city-state with limited land and no natural resources, has long understood the necessity of resource efficiency. Waste management is not an option but a matter of national survival. Under its Zero Waste Masterplan, Singapore has set an ambitious goal to increase its overall recycling rate to 70% by 2030, with a specific focus on construction and demolition waste (CDW).

The country has established a highly efficient, state-supported system for processing CDW. Demolition waste is collected and sent to dedicated recycling facilities. There, it is sorted, and the concrete and masonry are crushed into recycled aggregates of various grades. A key policy driver has been the government's own procurement standards. The Building and Construction Authority (BCA) of Singapore mandates the use of recycled materials in many government projects. For example, specific percentages of Recycled Concrete Aggregate (RCA) are required in non-structural concrete applications for public sector developments.

This top-down approach has created a stable, guaranteed market for recycled aggregates, incentivizing private companies to invest in the necessary crushing and processing technology. As a result, Singapore now recycles over 99% of its CDW (National Environment Agency, 2022). The recycled aggregates are used in road construction, backfilling, and, increasingly, in the production of new concrete and precast components. Singapore's success demonstrates how strong government leadership, clear regulatory targets, and the use of public procurement as a market-creation tool can rapidly accelerate the transition to a circular economy.

The UAE's Green Building Codes: Mandating Recycled Content

The United Arab Emirates, particularly the emirates of Dubai and Abu Dhabi, has undergone one of the most rapid construction booms in human history. This rapid development has also generated vast quantities of construction waste. Recognizing this challenge, the authorities have integrated circular principles into their green building regulations.

In Dubai, the "Al Sa'fat" Green Building Rating System is mandatory for all new constructions. The regulations include specific credits and requirements related to waste management and material sourcing. For instance, projects are required to divert a minimum percentage of construction waste from landfills. More importantly, the system awards points for using materials with a specified recycled content. This creates a direct market pull for products like steel rebar made from scrap metal or concrete blocks that incorporate fly ash or recycled aggregates.

Similarly, Abu Dhabi's "Estidama" (Arabic for 'sustainability') Pearl Rating System has requirements for both construction waste reduction and the use of recycled materials. To achieve a higher Pearl rating—which can be linked to faster building permits or other incentives—developers must demonstrate that a certain percentage of the total material cost comes from recycled sources. These regulations have spurred the growth of local recycling industries, including advanced facilities for processing CDW into usable aggregates and other products. The UAE's approach shows how market-based rating systems can effectively nudge a massive construction industry toward more circular practices without overly prescriptive mandates, allowing for innovation and flexibility.

Emerging Opportunities in Vietnam and Saudi Arabia

While Singapore and the UAE are established leaders, other major economies in their respective regions are beginning to embrace the circular economy, creating immense opportunities for forward-thinking businesses.

- Vietnam: With its rapid urbanization and industrial growth, Vietnam is facing significant challenges with waste management. The government has recognized this in its National Strategy on Green Growth, which calls for promoting recycling and sustainable production. The demand for building materials is immense, and the price of virgin materials like sand is rising sharply due to over-extraction. This creates a perfect economic storm that favors the adoption of circular materials. There is a burgeoning opportunity for companies to establish facilities for producing blocks and concrete using industrial by-products (from the country's many factories and power plants) and the growing stream of CDW from urban redevelopment.

- Saudi Arabia: As part of its ambitious Vision 2030 plan, Saudi Arabia is undertaking giga-projects like NEOM and the Red Sea Project. These projects are being designed with sustainability as a core principle from the outset. There is a strong emphasis on minimizing environmental impact, which includes a focus on waste management and circular material flows. For example, the developers of the Red Sea Project have committed to diverting the vast majority of their construction waste from landfills. This creates a massive, localized demand for recycling technologies and circular products. A company that can set up an on-site facility to process construction waste into high-quality blocks using a would be perfectly positioned to capitalize on this state-driven push for a new, more sustainable model of development.

These cases, from the established to the emerging, illustrate a clear trend. The circular economy is moving from the margins to the mainstream, driven by a combination of environmental necessity, regulatory pressure, and powerful economic logic.

Overcoming the Hurdles: A Pragmatic Look at Implementation Challenges

While the promise of the circular economy is immense, the transition from a linear to a circular model is not without its difficulties. Acknowledging and proactively addressing these challenges is crucial for any business seeking to succeed in this space. It requires not just technological investment but also a shift in logistics, quality assurance, and, most importantly, market perception. A clear-eyed, pragmatic approach is essential for navigating this new terrain.

Overcoming Logistical Hurdles in Waste Collection and Processing

The adage "garbage in, garbage out" is acutely relevant to the circular economy. The quality of a recycled material is directly dependent on the quality of the waste stream from which it is derived. One of the first major hurdles is the effective segregation of waste at the source. On a typical demolition site, concrete, steel, wood, plastic, glass, and gypsum are often mixed into a single, heterogeneous pile of rubble. Separating these materials after the fact is difficult, expensive, and often results in contaminated, low-quality recyclates.

- Source Separation: The solution begins with better practices on-site. This requires training demolition crews to deconstruct buildings layer by layer and to place different materials into separate bins or piles. This "soft" deconstruction is more labor-intensive than using a wrecking ball but is fundamental to preserving material value.

- Reverse Logistics: A new logistical network—a "reverse logistics" chain—is needed to transport these segregated materials from the construction or demolition site to the appropriate recycling facility. This involves coordinating transport, finding storage or consolidation points, and ensuring a steady flow of materials to keep processing plants operating efficiently. In sprawling cities, traffic and transport costs can be a significant factor.

- Processing Infrastructure: Establishing a recycling facility itself is a major undertaking. It requires space, permits, and significant capital investment in equipment like crushers, screens, magnetic separators, and potentially more advanced optical or density-based sorting systems. The location of these facilities is critical; they need to be close enough to the sources of waste and the end markets for the recycled products to minimize transportation costs.

For a business, this means thinking beyond the factory gate. It may involve forming partnerships with demolition companies to ensure a supply of well-segregated waste or even vertically integrating to control the entire chain from deconstruction to new product manufacturing.

Addressing Quality Control and Standardization Concerns

Perhaps the single greatest barrier to the widespread adoption of circular materials is skepticism about their quality and consistency. Architects, engineers, and builders are professionally and legally responsible for the safety and durability of their structures. They are understandably hesitant to use materials that they perceive as variable or inferior to their virgin counterparts.

To overcome this, rigorous quality control and adherence to standards are non-negotiable.

- Testing and Certification: A circular material producer must invest in a robust quality management system. This means regular testing of both incoming waste streams and outgoing final products. For a producer of recycled aggregate, this involves testing for properties like gradation, density, water absorption, and the presence of contaminants. For a block manufacturer, it means testing the compressive strength, dimensions, and durability of the finished blocks to ensure they meet or exceed local building codes.

- Developing Standards: In many regions, specific standards for circular materials are still under development. Businesses can play a proactive role by working with industry associations and government bodies to help establish these standards. Clear, reliable standards give specifiers the confidence they need to incorporate these materials into their designs. When a product is certified to a national or international standard (e.g., ASTM or EN standards), it moves from being a "recycled material" to simply being a "material" that meets a certain performance specification.

- Transparency and Data: Providing clear documentation for your products is essential. This is where concepts like material passports become powerful. A data sheet that clearly states the recycled content, performance characteristics, and test results for a batch of concrete blocks builds trust and allows engineers to make informed decisions.

A commitment to quality cannot be an afterthought; it must be the core of the business strategy. The goal is to produce a circular product that is not just "good enough" but is demonstrably equal or superior to the conventional alternative.

Shifting Mindsets: From Skepticism to Adoption

Beyond the technical and logistical challenges lies a more intangible but equally important hurdle: the human element. The construction industry is, by nature, conservative. Practices are passed down through generations, and there is a natural inertia that favors the "tried and true." Convincing a seasoned contractor or a skeptical client to embrace a new material or method can be a significant challenge.

- Education and Demonstration: Overcoming this inertia requires education. This can take the form of workshops, seminars, and the publication of clear, accessible technical literature. Case studies and demonstration projects are particularly powerful. When people can see and touch a high-quality building constructed with circular materials, it demystifies the concept and provides tangible proof of its viability.

- Highlighting the "Co-Benefits": The conversation should not be limited to environmentalism. While sustainability is important, the economic arguments are often more persuasive. Frame the discussion around cost savings from reduced material procurement, the marketing advantage of a "green" building, or the long-term durability benefits of using materials like fly ash concrete.

- Building a Community of Practice: Fostering collaboration is key. When architects, engineers, contractors, material producers, and policymakers work together, they can share knowledge, solve common problems, and build momentum. Joining industry associations and participating in green building councils can help build a network of allies and early adopters.

The journey to a circular economy is a marathon, not a sprint. It requires patience, persistence, and a deep understanding of both the technical and human dimensions of change. By anticipating these challenges and developing clear strategies to address them, businesses can position themselves not just as participants but as leaders in this critical transformation.

Building the Business Case: The Financial Logic of Circularity

While the ethical and environmental arguments for a circular economy are compelling, for a business to thrive, the numbers must add up. The decision to invest in new machinery, retool processes, and adopt new materials must be grounded in sound financial reasoning. Fortunately, the business case for the circular economy in building materials is not based on altruism; it is built on a foundation of cost reduction, new revenue generation, and long-term risk mitigation. For the pragmatic business owner in 2026, embracing circularity is simply smart business.

Reducing Raw Material Procurement Costs

The most direct and immediate financial benefit of adopting a circular model is the reduction in spending on virgin raw materials. In a traditional linear operation, materials are a major component of the cost of goods sold. The prices of cement, sand, gravel, and steel are subject to market fluctuations, supply chain disruptions, and the ever-increasing costs of extraction and transportation.

By substituting these virgin materials with circular alternatives, a business can significantly insulate itself from this volatility and lower its input costs.

- Waste as a Feedstock: Industrial by-products like fly ash and slag are often available at a much lower cost than Portland cement. In some cases, a power plant or steel mill may even pay a nominal fee for you to haul away their "waste," turning a material cost into a revenue stream.

- On-Site Recycling: For construction and demolition companies, the savings are even more pronounced. By investing in mobile crushing and screening equipment, a company can process concrete rubble on-site to produce recycled aggregate for the new project. This creates a double saving: it eliminates both the cost of transporting the rubble to a landfill and paying tipping fees, and it eliminates the cost of purchasing and transporting virgin aggregate to the site.

- Example Calculation: Consider a medium-sized block manufacturer producing 5,000 blocks per day. A standard block mix might contain 15% cement. If they can replace 30% of that cement with lower-cost fly ash, the daily savings on this one material alone can be substantial. Over the course of a year, these savings can amount to tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars, directly improving the company's profit margin.

Generating New Revenue Streams from Waste

The circular economy doesn't just reduce costs; it creates entirely new opportunities for revenue. It reframes waste streams not as a disposal problem but as a product line.

- Selling Recycled Materials: A demolition company that invests in sorting and processing can sell salvaged materials to other users. High-quality steel beams, architectural elements, and clean, graded recycled aggregates can all be sold into the market, generating income from what was previously a liability.

- Offering "Green" Products at a Premium: As market awareness and green building regulations grow, there is an increasing willingness to pay a premium for sustainable products. Concrete blocks with a high recycled content and a lower embodied carbon footprint can be marketed as a premium product to environmentally conscious clients or projects aiming for high green building certification ratings (e.g., LEED, BREEAM, Estidama). This allows a producer to capture more value from their output.

- Providing Services: Businesses can expand beyond manufacturing to offer circular economy services. This could include providing on-site crushing services for large construction projects, offering deconstruction and material salvage consulting, or establishing a trading platform for second-hand building materials.

By thinking creatively, companies can move from being simple manufacturers to being integrated solutions providers for the circular built environment, unlocking multiple streams of income.

Accessing Green Financing and Government Incentives

Governments and financial institutions are increasingly recognizing both the risks of the linear economy and the opportunities of the circular one. This is translating into tangible financial incentives for businesses that adopt sustainable practices.

- Green Loans and Bonds: Many banks now offer "green loans" with more favorable interest rates or terms for projects and investments that meet specific environmental criteria. Investing in a new, energy-efficient block making machine or a recycling facility could qualify a business for such financing, lowering the cost of capital.

- Government Grants and Subsidies: To accelerate the transition, governments may offer grants or subsidies for companies investing in recycling technology or for research and development into new circular materials. These programs can significantly de-risk the initial investment.

- Tax Incentives: Tax policies can also be used to encourage circularity. This might include tax credits for using recycled materials, accelerated depreciation for recycling equipment, or higher taxes on landfilling waste (which makes recycling more economically attractive by comparison).

- Carbon Markets: As carbon pricing and emissions trading schemes become more common, the lower embodied carbon of circular materials becomes a direct financial asset. A producer of low-carbon concrete blocks may be able to generate carbon credits that can be sold, creating another revenue stream.

When building the financial model for a circular venture, it is crucial to research and account for these available incentives. They can have a significant positive impact on the project's return on investment (ROI) and payback period, making an already attractive proposition even more compelling. The financial logic is clear: the circular economy is not a cost center, but a profit center for the resilient and forward-looking enterprise.

Gazing into the Future: Innovations on the Horizon

The circular economy in 2026 is a dynamic and rapidly evolving field. While we have focused on the established and commercially viable technologies of today, it is equally important to keep an eye on the horizon. The innovations that are currently in the laboratory or in early-stage trials will shape the industry of the next decade, presenting both new challenges and extraordinary opportunities. For a business leader, understanding these future trends is not just an academic exercise; it is essential for long-term strategic planning.

3D Printing with Recycled Materials

Additive manufacturing, or 3D printing, is poised to revolutionize construction. Large-scale robotic printers can already construct building shells by extruding layers of a specialized concrete mix. The next frontier in this technology is the integration of recycled materials into the printing "ink."

Researchers are developing printable concrete formulations that incorporate finely ground demolition waste, fly ash, or even recycled plastic fibers. This technology offers several profound advantages for a circular economy. It is a highly efficient process that generates almost zero waste, as material is only deposited where it is needed. It also allows for the creation of complex, optimized geometries that would be impossible with traditional formwork, potentially reducing the total amount of material required for a structure.

Imagine a future where a mobile 3D printing robot arrives at a demolition site, consumes the crushed and processed rubble from the old building, and prints the shell of the new one. This represents a near-perfect, on-site closed loop. While still in its infancy for mainstream applications, the rapid progress in this field suggests that by the mid-2030s, it could become a viable construction method, creating a new market for highly processed, fine-grade circular materials.

Bio-based and Self-Healing Materials

Another exciting frontier is the development of materials that mimic biological processes. This field of biomimicry is leading to innovations that could further reduce our reliance on extracted resources.

- Bio-based Materials: These are materials derived from living organisms. Cross-laminated timber (CLT) made from sustainably harvested wood is already a mature technology, acting as a carbon sink within buildings. Newer innovations include insulation panels grown from mycelium (the root structure of fungi) and bioplastics derived from algae or agricultural waste. These materials are renewable and often biodegradable at the end of their life.

- Self-Healing Materials: Nature has an incredible ability to repair itself. Researchers are developing materials that can do the same. Self-healing concrete is a leading example. In one approach, tiny capsules containing a healing agent (like a polymer or an epoxy) are embedded in the concrete mix. When a micro-crack forms, it ruptures the capsules, releasing the agent which then fills and seals the crack, preventing water ingress and corrosion of the reinforcing steel. Another approach uses bacteria. Spores of specific bacteria and their food source (calcium lactate) are added to the mix. When a crack allows water to enter, the bacteria are activated, and their metabolic process produces limestone, which automatically seals the fissure (Jonkers, 2011). This technology could dramatically extend the lifespan of concrete structures, delaying the need for repair or demolition and keeping materials in use for much longer.

The Role of AI and Robotics in Deconstruction

The process of dismantling a building to salvage its components is currently labor-intensive and requires specialized skills. The future of deconstruction will likely be dominated by artificial intelligence and robotics.

Imagine a "deconstruction robot" equipped with advanced sensors (like LiDAR and hyperspectral cameras) and guided by an AI. This robot could scan a building and, by accessing its material passport data, create a detailed disassembly plan. It could then autonomously move through the structure, using precision tools to cut welds, unscrew bolts, and carefully remove panels, beams, and windows without damaging them.

The AI would be able to identify and sort materials in real-time, placing them into designated bins for reuse or recycling. This would make the deconstruction process faster, safer, and far more efficient than manual methods, dramatically improving the economic viability of urban mining. This synergy between digital information (material passports) and physical automation (robotics) represents the ultimate expression of a data-driven circular economy.

While these technologies may seem like science fiction, the pace of change is accelerating. Businesses that build a flexible and adaptable foundation today—by embracing data, investing in quality, and fostering a culture of innovation—will be the ones best positioned to harness these transformative technologies as they become the new standard.

Perguntas frequentes (FAQ)

What is the circular economy in building materials?

It is an economic model that aims to eliminate waste in the construction industry by keeping materials in use for as long as possible. Instead of the traditional "take-make-dispose" approach, it focuses on designing buildings for disassembly, reusing components, and recycling materials back into high-value products.

Are building materials made from waste as strong as new ones?

Yes, when produced correctly. The key is rigorous quality control. For example, concrete blocks made with fly ash or properly processed recycled concrete aggregate can meet or even exceed the strength and durability standards of blocks made only with virgin materials. The performance depends on the quality of the recycled input, the mix design, and the manufacturing process.

Is it more expensive to build with circular materials?

Not necessarily. While some salvaged components or specialized green products might have a higher initial purchase price, the overall project cost can often be lower. This is because using recycled materials can drastically reduce spending on new raw materials and eliminate waste disposal fees. Government incentives and green loans can also improve the financial case.

What is the most important first step for a construction business to become more circular?

The most impactful first step is to improve waste segregation on-site. By separating different waste streams (concrete, metal, wood, etc.) at the source, you dramatically increase their potential for recycling and reuse. This simple change in practice is fundamental to preserving material value and is more about process management than large capital investment.

What kind of machinery is needed to make blocks from waste?

You need a robust concrete block making machine designed to handle variable materials. Key features include a powerful vibration system, high-pressure hydraulics, and a PLC control system for precise batching. A static hydraulic block machine is ideal for large-scale, high-quality production, as it can be integrated into a full production line that manages mixing, curing, and handling.

How does the circular economy benefit the environment?

It reduces the need to extract virgin raw materials, which saves energy, conserves natural resources, and protects ecosystems. It significantly cuts down on the amount of waste sent to landfills, reducing land use and pollution. By using industrial by-products like fly ash to replace cement, it also dramatically lowers the greenhouse gas emissions associated with construction.

Can I use 100% recycled materials in new concrete?

While using 100% recycled aggregate is technically possible for some applications, it is not common for structural concrete. A more typical approach is to replace a percentage (e.g., 20-50%) of the virgin sand and gravel with high-quality recycled aggregate. This blended approach ensures consistent performance while still achieving significant environmental and economic benefits.

A Concluding Reflection on Our Built Future

The transition to a circular economy in building materials represents more than a technical or economic shift; it is a profound re-evaluation of our relationship with the material world. It asks us to see the buildings we inhabit not as temporary conveniences destined for a landfill, but as valuable repositories of resources—urban mines waiting to be tapped. It challenges us to move beyond a short-term, extractive mindset and to adopt a long-term, custodial one, where we act as stewards of the materials we use.

For businesses operating in the dynamic markets of Southeast Asia and the Middle East, this is not a burden but a historic opportunity. The pressures of rapid urbanization, resource constraints, and a growing environmental consciousness are not obstacles; they are the very market forces that make the circular model so compelling. The demand for sustainable infrastructure is no longer a niche, but the emerging standard.

By embracing waste as a resource, investing in the technologies that transform it into value, and committing to the rigorous standards that ensure quality, companies can do more than just improve their bottom line. They can become central players in building a more resilient, more efficient, and more sustainable future. The path forward is not a straight line to disposal, but a continuous circle of innovation and regeneration.

Referências

Debacker, W., & Manshoven, S. (2016). Materials passports: The key to a circular economy. VITO/OVAM.

Ellen MacArthur Foundation. (2013). Towards the circular economy: Economic and business rationale for an accelerated transition. https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/TCE_Ellen-MacArthur-Foundation_9-Dec-2015.pdf

hfblockmachine.com. (n.d.-a). QT4-25. Retrieved October 26, 2026, from

hfblockmachine.com. (n.d.-b). QT10-15. Retrieved October 26, 2026, from

hfbrickmachine.com. (n.d.). Concrete block and brick making machine manufacturer. Retrieved October 26, 2026, from

Jonkers, H. M. (2011). Bacteria-based self-healing concrete. Heron, 56(1/2), 1-12.

Mehta, P. K. (2014). Betão de alto desempenho e alto volume de cinzas volantes para o desenvolvimento sustentável. Em Actas da Conferência Internacional sobre Materiais e Tecnologias de Construção Sustentáveis.

National Environment Agency. (2022). Recycling statistics. Singapore. https://www.nea.gov.sg/our-services/waste-management/waste-statistics-and-overall-recycling

Obla, K. H. (2021). A new perspective on recycled aggregates. National Ready Mixed Concrete Association.

Pearce, D. W., & Turner, R. K. (1990). Economics of natural resources and the environment. Johns Hopkins University Press.